The Circular Economy: Origins, Opportunities, and Obstacles

Introduction to CE origins, opportunities, and barriers to adoption

Background

I did well on this essay. It provides background on the theory behind Circular Economy, practical exploitations of the theory by existing business models, and obstacles to adoption.

The prompt is quite long and informs why I chose to tackle a broad remit in ≈2000 words.

“The Circular Economy is a disruptive innovative economic model that relates to government policy, businesses and consumers, which is restorative or regenerative by design, structure, and objective: products, components, and materials should continuously add, recreate, and preserve value at all times. This is in order to use as few resources as possible, for as long as possible, reuse as much of the components as possible, extract as much value from those resources in the most effective way possible, and then recover and regenerate as much of those materials and products at the end of their useful life when and if possible.”

Discuss and analyse the above statement

Analyse how a Circular Economy model can contribute to achieving economic growth.

Discuss the challenges and opportunities associated with applying such a model

Introduction

The Circular Economy has experienced increasing academic interest and wider popularity over the past few years (Ruiz-Real et al., 2018) — likely due to the worsening climate crisis (Milman, 2022). This essay will discuss the meaning of the Circular Economy, how it relates to economics and other areas of study, examples of its ability to drive economic growth, and future challenges and opportunities associated with its implementation. This essay defines the Circular Economy as an economic and social model that prioritises efficient asset use and serves as an alternative to linear production’s waste and negative climate impact. This essay argues that the Circular Economy can generate economic growth, that its all-encompassing nature is a barrier to adoption, and that shifting social attitudes provide hope for its adoption.

Origin and remit of the Circular Economy

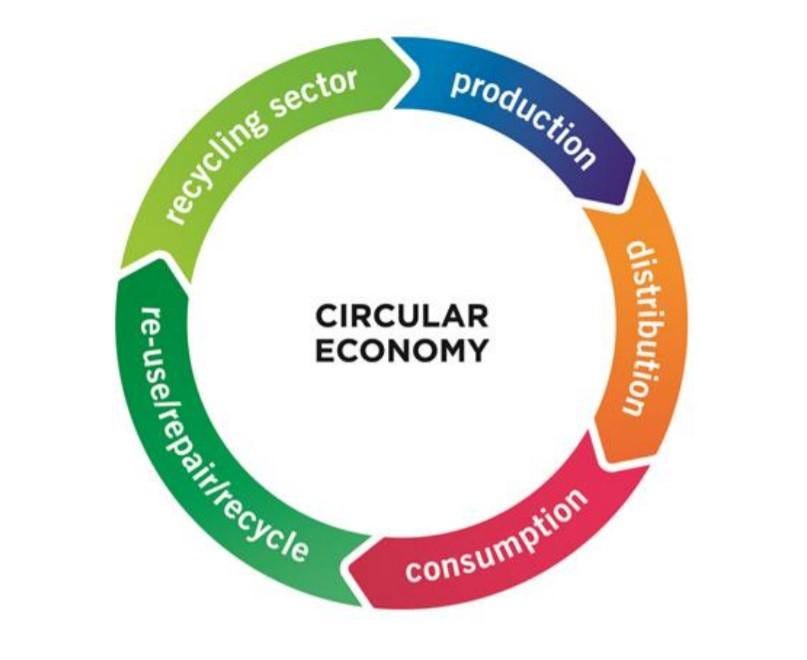

It is necessary to understand the status quo to understand the disruptive and innovative nature of the Circular Economy. The development of the Circular Economy was reactive to the linear model of production and consumption — the current dominant model. Lacey et al. (2020) describe the Linear Economy as the traditional industrial model where raw materials are extracted, turned into products, and likely thrown away as non-recyclable waste after consumption. Figure 1 below represents this model’s lifecycle.

There are two major existential issues with this industrial model:

Humanity cannot sustain this pattern of consumption owing to resource scarcity. Resource consumption is 1.7 times the earth’s carrying capacity, meaning humanity consumes 70% more natural resources than regenerating each year (Earth Overshoot Day, 2022).

Humanity will cause its extinction if it continues this pattern of consumption and pollution. Half of the world’s population will be living in a water-stressed area by 2025 (World Health Organization, 2019). Moreover, habitat loss has led to one-fifth of the earth’s vegetated surface becoming less productive during the past 20 years (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2019).

These facts demonstrate the need for a sustainable industrial model that can secure humanity’s future, leading to the conception of a Circular Economy.

The Circular Economy recognises that humanity cannot afford to squander the planet’s vital resources and that humanity must take care of its environment. The Circular Economy aims to curb inefficient resource use and pollution by ensuring waste is not a byproduct of the production cycle, as documented above. The linear production model has waste as its final stage. Contrastingly, the Circular Economy emphasises durable design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling to ensure resource preservation, maximise efficiency, and avoid pollution (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). Examining the Circular Economy’s origins reveals fundamental flaws in the Linear Economy and an urgent need to introduce a new economic model to ensure humanity and the planet’s wellbeing. The Circular Economy, a direct response to this problem, provides a solution by emphasising avoiding waste and pollution while preserving resources and maximising efficiency.

Politics, policy, business, and economics are all intimately connected with the Circular Economy and each other, as they all relate to the distribution of resources. Laswell (1936) defines politics as who gets what, when, and how — describing politics as a system by which society distributes resources. Government policy is the mechanism by which governments can mandate rules around the distribution of resources through their monopoly on the legitimate use of force (Weber et al., 2004). Economics is the study of how to deploy scarce resources efficiently in a world of unlimited wants (Samuelson & Nordhouse, 1995) — which encompasses both the allocation and use of resources by businesses and consumers. The binding thread that ties these subjects together is resources. Given that the central premise of the Circular Economy is the efficient use of resources to prevent waste, the Circular Economy links inextricably to all these topics.

Economic Opportunity in the Circular Economy

The existence of waste in the Linear Economy logically means the production process is inefficient and thus provides suboptimal economic returns. A perfectly efficient product would not produce any waste and only provide what is required. Since the Circular Economy seeks to eliminate or minimise waste and improve the efficiency of resource use, economies adopting circularity should experience economic growth as they are using resources more efficiently and producing more with the same level of resource use or less. Although this may intuitively sound reasonable, it is worth examining the success of businesses that adopt aspects of the circular economy. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2015) analysed activities or business models that contribute to creating a circular economy, resulting in the ReSOLVE framework, which sets forth ways in which companies can pursue circular strategies and growth initiatives. Figure 3 below illustrates these strategies and provides examples of companies adopting them.

Companies that follow strategies discussed in the ReSOLVE framework should succeed if circular strategies contribute to economic growth. The next step is to examine companies with circularity in their business models and evaluate their success.

Asset Sharing

The typical European Vehicle spends 92% of its time parked and only carries 1.5 people per trip (The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015) — presenting an example of poor resource use. Ridesharing and ride-hailing business models represent the “S” in the ReSOLVE framework — facilitating increased asset use through sharing. Esposito et al. (2015) outline how modern ride-sharing and ride-hailing services eliminate many logistical barriers for vehicle owners to share or rent their vehicles to other individuals. The advance of these businesses facilitates the more efficient use of existing assets and increased competition in the taxicab market. Consequently, these business models put downward pressure on transport prices through increased vehicle supply — raising the incentive to use these services rather than purchase a car. Fewer individuals buying cars lead to decreased production, fewer cars on the road, less air pollution, and decreased primary material extraction (Esposito et al., 2015).

The successful adoption of ride-sharing and ride-hailing business models should lead to consistent sector growth and more competition in the taxicab market owing to more market entrants. The ride-hailing app sector has seen near consistent year on year growth across all geographies since 2015 (Curry, 2022). The exception to this constant growth has been the COVID-19 pandemic — as reflected in the research of Du and Rakha (2020). Figure 4 below displays the economic growth experienced by ride-hailing companies within the United States.

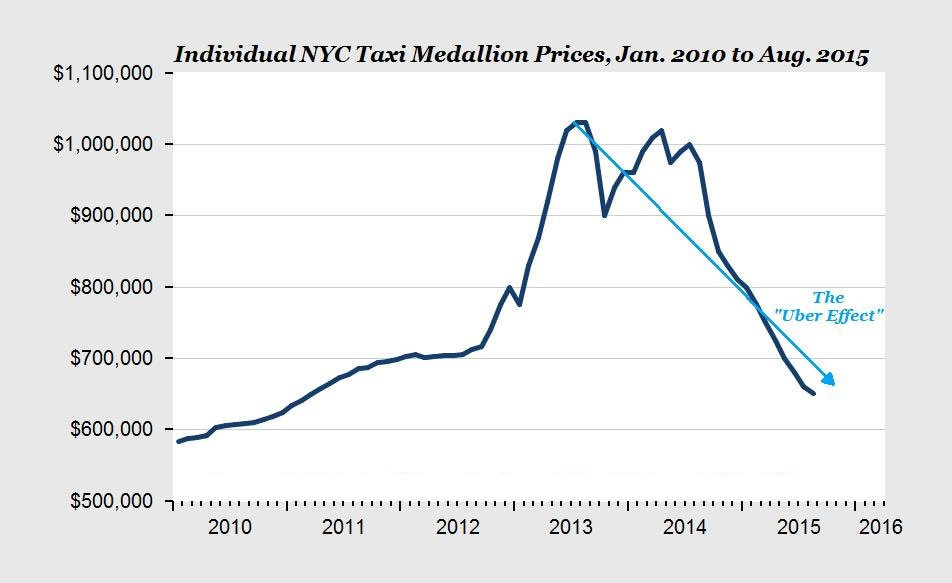

The growth of the ride-hailing market has accompanied the decline of taxi licensing prices. Rubinstein (2014) notes that historically strict regulation constrains the number of taxicabs operating. At its peak, this led to New York City taxicab medallion prices (fixed-quantity license for operating a taxi) reaching over $1 Million (CB Insights Research, 2015). Once a highly sought after commodity, the taxicab medallion price tumbled with the rise of the ride-hailing economy, increased asset use, and mounting competition. Figure 5 below shows the rise and decline of taxi medallion prices over time. Today, the price of a New York City taxicab medallion sits at a comparatively meagre $80,000 (Khafagy, 2021)

The consistent growth experienced by companies harnessing the sharing economy and the increased competition in the market shows one way in which the circular economy can drive economic growth through more efficient asset use.

Digitalization

Representing “V” in the ReSOLVE framework, virtualization has seen a significant expansion since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the pandemic has stunted economic growth (Congressional Research Service, 2021), it may lead to more efficient asset use. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2015) documents that the average European office receives use only 35–40% of the time, even during working hours. This statistic represents an astonishing degree of waste and an exceptional opportunity for efficiency and economic growth increases.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic was a global catastrophe, it led to a paradigm shift in how individuals work. Video conferencing software became an immediate necessity for many businesses as offices became unsafe for workers — instantly virtualizing many workplaces. The growth experienced by video conferencing companies like Zoom is evident. Figure 6 shows a sharp rise in company revenue during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though the pandemic was a catalyst in accelerating Zoom’s growth, it does not mean their business model does not have value. Although Zoom’s revenue growth has started to slow (Reuters, 2021), their retained revenues suggest customers still find value in the product and value the virtualization of the workplace.

Statistics from UK businesses support the notion that companies value digitalizing the workplace. Looking towards the future, 24% of businesses intend to continue with a hybrid working or home working model (Office for National Statistics, 2021). In choosing to continue with this mode of work, these businesses cited improved staff wellbeing (79.9%), reduced overheads (49.1%), and improved productivity (48.3%) as the top three reasons for permanently increased homeworking arrangements (Office for National Statistics, 2021). Workers that could work from home saw benefits in their wellbeing, and businesses experienced financial and productivity benefits.

Business productivity and financial benefits and Zoom’s revenue growth suggest that digitalization, a facet of the circular economy, can significantly contribute to economic growth. These benefits become greater once considering further possible economic growth stemming from the repurposing of commercial premises, which were already inefficiently used (The MacArthur Foundation, 2015).

Obstacles and Opportunities in the Circular Economy

As discussed, politics, policy, business, and economics are all intimately interconnected. Therefore, dislodging the Linear Economy and implementing the Circular Economy will require a complete change in society’s organization. Unfortunately, this change will not be easy. Runciman (2018) documents that this type of change does not occur without major social and political upheaval. It required the most severe pandemic since the 1918 Spanish Influenza (Adams, 2022) for the office digitalization example discussed above to materialize. With that, 50% of businesses in the UK still choose to operate commercial premises and require workers to attend in person (Office for National Statistics, 2021). Although this example shows great potential for economic growth by embracing circularity and more efficient asset use, it also illustrates how difficult it is to create change.

Despite the challenges inherent in changing existing norms, there is hope for the future. Attitudes towards climate change are quickly shifting amongst many countries. Fagan & Huang (2019) show that concern over climate change has rapidly increased in a short timeframe in Figure 7 — found below.

Moreover, the ability to take more progressive action towards tackling climate change and implementing circular business models seems to be more likely as time passes. Funk (2021) indicates that younger generations are more concerned and willing to tackle climate change — as displayed in Figure 8.

Although implementing the Circular Economy and tackling climate change will require major societal transformations, there is hope for the future owing to shifting attitudes and increased willingness amongst younger generations.

Conclusion

The Circular Economy is a response to the increasing threat of climate change and the pollution caused by linear production. As an alternative economic model of production, the Circular Economy directly impacts business, politics, policy, and economics. The Circular Economy promises greater economic growth through more efficient asset use. This essay provides examples of potential growth by discussing the ride-sharing/ride-hailing industry and office virtualization. Although the Circular Economy has the potential to unlock economic growth, its all-encompassing nature necessitates major upheaval in multiple areas of society for its implementation. Despite the difficulty that the Circular Economy’s implementation entails, there is hope for the future insofar as social attitudes are quickly changing and younger generations are more willing to tackle climate change and implement the Circular Economy.

Bibliography

Adam, D. (2022) The pandemic’s true death toll: millions more than official counts [online]. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00104-8 (Accessed 24 January 2022).

CB Insights Research (2015) The ‘Uber Effect’ Is Crushing Taxi Medallion And Stock Prices [online]. Available from: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/public-stock-driven-uber/ (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Congressional Research Service (2021) Global Economic Effects of COVID-19. [online]. Available from: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46270.pdf (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Curry, D. (2022) Taxi App Revenue and Usage Statistics (2022) [online]. Available from: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/taxi-app-market/ (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Du, J. & Rakha, H. (2020) COVID-19 Impact on Ride-hailing: The Chicago Case Study. Transport Findings. [Online]. Available from: https://findingspress.org/article/17838-covid-19-impact-on-ride-hailing-the-chicago-case-study (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Earth Overshoot Day (2022) Past Earth Overshoot Days — #MoveTheDate of Earth Overshoot Day [online]. Available from: https://www.overshootday.org/newsroom/past-earth-overshoot-days/ (Accessed 16 January 2022).

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2015) Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe.

Esposito, M., Tse, T. and Soufani, K. (2015) Is the Circular Economy a New Fast-Expanding Market?. Thunderbird International Business Review. [Online] 59 (1), 9–14.

Fagan, M. & Huang, C. (2019) A look at how people around the world view climate change [online]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/18/a-look-at-how-people-around-the-world-view-climate-change/ (Accessed 25 January 2022).

Funk, C. (2021) Key findings: How Americans’ attitudes about climate change differ by generation, party and other factors [online]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/26/key-findings-how-americans-attitudes-about-climate-change-differ-by-generation-party-and-other-factors/ (Accessed 25 January 2022).

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (2019) The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture 2019 [online]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/state-of-biodiversity-for-food-agriculture/en/ (Accessed 16 January 2022).

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. and Hultink, E. (2017) The Circular Economy — A new sustainability paradigm?. Journal of Cleaner Production. [Online] 143757–768.

Lacy, P., Long, J. and Spindler, W. (2020) The Circular Economy handbook. 1st edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Iqbal, M. (2022) Zoom Revenue and Usage Statistics (2022) [online]. Available from: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/zoom-statistics/ (Accessed 24 January 2022).

Khafagy, A. (2021) NYC Yellow Taxi Medallion Crisis, Explained [online]. Available from: https://documentedny.com/2021/11/23/taxi-cab-medallion-explained/ (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Laswell, H. (1936) Politics; who gets what, when, how. London: McGraw-Hill Book Co.

Milman, O. (2022) Nearly quarter of world’s population had record hot year in 2021, data shows [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jan/13/hot-year-temperatures-climate-crisis-2021 (Accessed 15 January 2022).

Office for National Statistics (2021) Business and individual attitudes towards the future of homeworking, UK: April to May 2021. [online]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/businessandindividualattitudestowardsthefutureofhomeworkinguk/apriltomay2021 (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Reuters (2021) Zoom shares fall after results as Wall Street turns cautious on growth [online]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/technology/zoom-beats-quarterly-revenue-estimates-2021-11-22/ (Accessed 24 January 2022).

Rubinstein, D. (2014) Uber, Lyft, and the end of taxi history [online]. Available from: https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2014/10/uber-lyft-and-the-end-of-taxi-history-017042 (Accessed 23 January 2022).

Ruiz-Real, J., Uribe-Toril, J., Valenciano, J. and Gázquez-Abad, J. (2018) Worldwide Research on Circular Economy and Environment: A Bibliometric Analysis. International Journal of Environmental and Public Health. [Online] 15 (12), 2699. [online]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6313700/ (Accessed 15 January 2022).

Runciman, D. (2018) How democracy ends. London: Profile Books.

Samuelson, P. & Nordhaus, W. (1995) Economics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Soufani, K. (2022) Circular Economy: Entrepreneurial Science & Innovation Policy.

Weber, M., Owen, D. and Strong, T. (2004) The vocation lectures. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub.

World Health Organization (2019) Drinking-water [online]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water (Accessed 16 January 2022).